General Process of Personal Experience#

Actually, it was already past 11.26 when I saw the news in my social circle at half past midnight—someone was live blogging a memorial event on Urumqi Middle Road. Before I set off, I wasn't sure if the event had already ended, but in any case, I decided to take a taxi there. I arrived around one o'clock, alone, without calling anyone else.

I was indeed a bit scared before going. The decision to go out was very rushed, my phone was almost out of battery, and I had just grabbed a power bank. I didn't take a bag; I stuffed the power bank and my phone into my pocket, even simulating whether it would be convenient if I needed to run. As we approached a traffic light at an intersection near my destination, two police cars whizzed by. Watching the two police cars disappear, I felt a bit of fear about the uncertain road ahead.

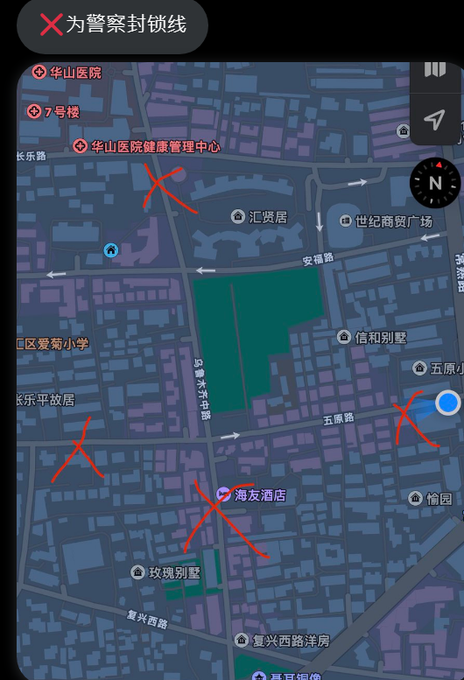

When the car reached the intersection of Urumqi Middle Road and Wuyuan Road, we could no longer proceed. The police had already set up a cordon, "the road is closed." So we turned onto Wuyuan Road and stopped. The cordon only restricted vehicles, and people could still move freely. I got out of the car and continued walking towards the intersection of Urumqi Middle Road and Anfu Road. At the intersection, I saw a FamilyMart, and since I was a bit hungry, I bought a rice ball to eat—mainly thinking that if I went in and got delayed, I might not get anything to eat.

As I approached the intersection of Anfu Road and Urumqi Middle Road, I could see many people gathered in the middle of Urumqi Middle Road, with many police officers standing nearby. I didn't know what was happening; everyone was taking photos and videos, and no police were stopping us from filming. Before I got close to the crowd, I first noticed a candle holder surrounded by candles and some flowers and wine under the street sign at the northwest corner of the intersection of Anfu Road and Urumqi Middle Road. I went to take a photo.

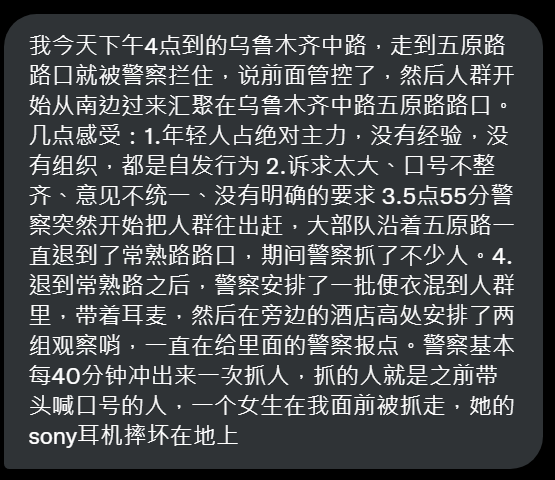

After taking the photo, I moved closer to the crowd. It seemed that there were two groups of people separated by the police cordon, but I didn't know what was inside the cordon; it seemed that only those who lived nearby were allowed to pass through. Later, I saw on Twitter that there were people skateboarding inside. I didn't know what had happened before I arrived, how people had come to be distributed as they were now; according to descriptions in my social circle, I only knew that at some point, someone in the crowd had started holding up white paper, and everyone followed suit. I couldn't estimate how many people had gathered; I just felt there were really a lot, probably at least a thousand.

Despite being in this land and city, seeing the candle holders and the large crowd of so-called "secret" gatherings in the night, I felt a strange sensation, as if I had entered a different dimension. It had been three years since I had seen so many people gathered together, even for something as simple as this. But to be honest, from the moment I arrived and saw the crowd, I wasn't scared at all. I felt there was nothing to fear; everything was so normal. People were just mourning normally, gathering normally, and the police seemed just as confused, not knowing what to do next, merely trying to maintain order, more like preventing a stampede. And the feeling of standing together with others really provided a natural sense of safety.

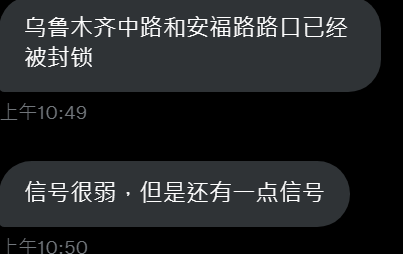

When I first approached the crowd, I heard someone leading a chant of the slogan left by the "Four Sealing Bridge Warrior" Peng Zaizhou: "No lockdown, we want freedom," and everyone echoed. Later, someone shouted, "Foolish Xi Jinping," but very few joined in, which led to a burst of laughter. Most people in sight were holding their phones to film, and what struck me was that no police shouted "No filming" (so all the pressure fell on the review departments of WeChat/Weibo/Douyin, etc.?). But then I thought about it and realized it made sense: everyone wanting to film for remembrance was reasonable, and under such a large gathering, without orders from above, it was logical for the police not to act rashly. Additionally, I noticed a woman in front of me holding a wine glass while standing in the crowd watching. During this time, I tried to send the video I filmed to my friends, but I found my phone couldn't connect to the internet.

Later, someone started singing the national anthem, and everyone responded together, "Arise, ye who refuse to be slaves..." Hearing the national anthem, I left the crowd intending to continue wandering around the outskirts. As I left, I saw a few people leaving like me, and I heard a young man laughing with someone next to him, saying, "I can't take it anymore." After leaving the crowd, I noticed quite a few people standing on the steps of the community railing watching from a distance, including a delivery guy in a Meituan uniform.

Not long after, I heard someone start questioning, "What are they sealing off?" "Why can't we go over there?" Then he shouted loudly, "Let us gather together," and after he shouted, some people echoed. Soon, people from both sides broke through the cordon, and the whole street could flow freely again. Shortly after the crowd dispersed, I heard someone shout, "Face-to-face group, 1124."

After the crowd dispersed, people were walking back and forth, taking photos around the candle holder. It turned out there was a larger memorial site on the north side (near Chang Le Road). 【【/todo image】】 While taking photos, I noticed that on the side of the candle holder away from the street, some people seemed to be standing still, mostly holding white paper partially covering their faces. Additionally, there were some small groups of people; I heard some gathered together saying, "Let's go have a drink"; I also heard others discussing what had just happened, "What I can't accept the most is that everyone just stands there and does nothing."

I continued to walk back and forth, and at this point, I felt the event was nearing its end. I strongly felt there was nothing to fear; everything was so normal—people were gathering normally, dispersing normally. Except for the increasing number of police arriving from all directions, everything was very normal. Many police officers were standing side by side on Anfu Road and Chang Le Road; I’m not good at estimating numbers, but I guessed there were over a hundred. Many police cars were also coming from the direction of Anfu Road, and I saw one police car with its trunk open; the police seemed unsure of what they were doing, and the trunk contained a large metal device, about the size of a suitcase, which I wondered might be related to signal jamming.

Returning to the candle holder and flowers under the street sign on Urumqi Middle Road that I mentioned earlier, many people had gathered here. I heard someone inside leading a gentle Uyghur song, and halfway through, two fashionable-looking Uyghur people who seemed to be passing by stopped, and one of them hummed along. At that moment, I felt, is this a requiem? It’s really so gentle.

After standing under the street sign for a while, I decided to go to the nearby convenience store to buy a bottle of wine. Unfortunately, there was no Dazhong Beer, so I just bought a bottle of beer. While waiting in line to pay, I noticed two or three workers (possibly road repair workers) around were buying instant noodles or eating instant noodles. One of them seemed to have just bought instant noodles and was about to soak them when the convenience store lady scolded him, "Go soak them over there; do you want me to help you?" At the same time, I heard a young man next to him say to his companion, "The person I fear the most since middle school is this convenience store lady, and it’s still the same now."

The whole scene had a bit of a late-night diner feel, everything so normal, noisy but full of life.

After buying, I walked through the crowd to place the beer next to other bottles, then returned to stand in the crowd. When I got back to the crowd, someone next to me shouted loudly, "Since everyone is here, let's not wear masks. Is it cold? If it's cold, let's gather together." I felt a bit ashamed; I took off my mask. Is it cold? It is a bit, but that’s not the main reason for wearing a mask. To be honest, I was still a bit scared, especially seeing everyone filming; I didn't want my face to be captured in someone else's camera.

After offering a bottle of beer, I prepared to leave, probably around two o'clock. Overall, I didn't stay long; for some reasons, it was inconvenient to be out too long; otherwise, I really wanted to stay longer to continue observing what would happen on this street.

In any case, I left, and as I walked a few steps away, a passerby spoke to me, "What’s going on over there?" I was a bit unsure and cautiously replied, "It's a memorial event. Mourning the fire in Urumqi a few days ago." "Oh... it's a memorial event?" "Yeah, you can go take a look," I said. He seemed startled, "I'm not going." Then he added playfully, "I'm an innocent bystander. You know, it's usually the innocent bystanders who suffer from unexpected disasters. I just passed by here after going to the hospital for a nucleic acid test." I casually responded to him a few times and then parted ways.

That was the end of my experience that night.

Additional Information from Other Sources#

Above, I have tried to describe in detail everything I witnessed, but for the sake of completeness, I will use the information I found online to fill in the entire story.

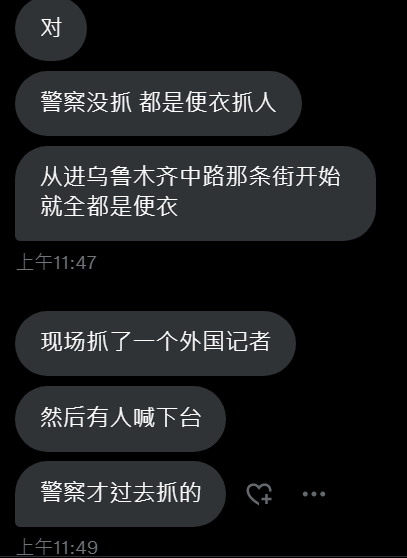

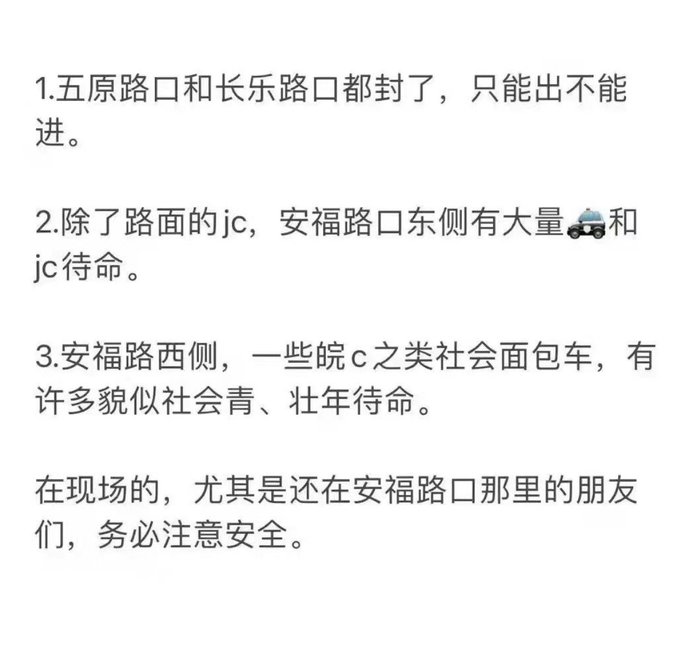

First, on the evening of 11.26, citizens passing through Urumqi Middle Road spontaneously organized a memorial event for the 11.24 Urumqi fire, but because the police were too scared and vigilant, the number of police gathered increased, and it eventually evolved into a large protest. Initially, the police were very restrained, but around 3 a.m., when there were not many people left at the scene, the police began to adopt strategies to disperse the crowd and arrest people; it was said that two vans were overloaded with people.

As the news spread further, on 11.27, others who heard the news rushed to Urumqi Middle Road to either mourn or continue protesting, and on that day, many police had gathered since the daytime. The police that day showed their teeth from the beginning, and the scene was more brutal. It was said that two buses of people were eventually arrested.

More reference resources are placed in the Appendix.

Feelings and Reflections#

First, why did I go?

The memorial event itself attracted me; the deceased are gone, and a small gathering to quietly mourn might heal more of the living, but we really need this kind of "self-comfort." Additionally, I certainly wouldn't be naive enough to think this was just a memorial event that would end here; I didn't know how things would develop, but I wanted to witness it firsthand. For example, I came across a saying on Twitter, "You see the flames of war on Twitter, but in reality, it's quiet." This sense of disconnection made me hold many unrealistic fantasies and also a lot of self-doubt; I wanted to see more clearly what was happening. In short, I had many feelings that night, which I will elaborate on below.

There is still much to learn related to struggle.

For instance, my most direct feeling was that I couldn't even estimate the number of people present, which should be a basic ability. Additionally, as I heard complaints, "I can't stand everyone just standing there"—we lack self-organization. Although this was indeed just a memorial event that unexpectedly turned into a protest or even a struggle, everyone had never had experience in struggle before, and it was normal not to be prepared.

To be honest, being there at the time, I felt very confused; I didn't know what I should do in a protest action. What slogans should I shout? Besides demands, is it reasonable to publicly express emotions? Should I echo? Should I film? What kind of purpose should I aim for, to let more people know that this was happening? Do we need a unified slogan? Would a unified slogan help us achieve our goals? Even further, are we ready to welcome the goals we are demanding? Do we need to be prepared? I don't know; my limited firsthand experience of so-called "street actions" only includes the BLM marches, which seemed more like everyone was just making a statement, and the struggle aspect wasn't stronger than what was happening now. I had no experience at all. At that moment, I wished I had more knowledge of protest cases, like what was happening in Iran.

Moreover, the signal jamming caught me off guard; there are so many P2P network knowledge discussions, but undoubtedly, the method of jamming signals is simply violent and destructive. I am sure that the signal jamming vehicles are just the beginning; if the police use tear gas, how should we protect ourselves? How can we avoid our friends being arrested by the police? How can we distinguish who our partners are and who are plainclothes police... We still have too many skills to learn.

Our road is still long.

As analyzed above, our experience in struggle is almost zero, and the historical events that can be compared to the political environment are probably only the spring and summer of 1989, but that was a failed attempt. Moreover, most of the people who took to the streets that night were young people who had never experienced June Fourth. Our struggle against the violent machine still requires more skills and experience.

Additionally, most of the participants that night were young people, and I even felt they were young intellectuals. As previously described, there were road repair workers around, but they were eating instant noodles in the convenience store and did not join us; office workers passing by were curious about the event but chose to avoid it and did not join us; the Meituan delivery guys seemed the most likely to join, but for now, they were just watching from the sidelines.

I also felt very clearly that everyone's demands were not unified, or rather, there were no clear demands. Some demanded no nucleic acid tests, no masks, and no lockdowns; some demanded the party to step down, but more people might just be venting their dissatisfaction.

After leaving the scene, I saw videos exposing people shouting "Communist Party, step down." To be honest, this is the part that confuses me the most. On one hand, I saw Twitter users excitedly expressing that they were surprised to hear such a significant political demand being shouted openly; this was indeed a very different movement. It got me excited along with the Twitter users. But on the other hand, from my brief experience at the scene, I didn't feel the atmosphere had reached that level. I don't know if this was something that happened before I arrived or after I left; I would guess it was after I left because the videos should have circulated quickly and not lagged for over an hour. But this is even stranger; when I left, the crowd's momentum had clearly dissipated, and I felt that most people at the scene did not have such "dangerous" demands. Jim described the experience at Liangmaqiao in this report, stating, "Some people on site tried to shout 'Communist Party step down,' but many would immediately stop them, saying we shouldn't talk about such radical slogans now. Everyone tacitly suppressed this, which is quite different from the situation on Urumqi Middle Road in Shanghai." However, I pessimistically believe that there isn't much difference on Urumqi Middle Road in Shanghai; shouting this slogan was more likely because people hadn't had time to think, so the emotional outburst was more direct, and no videos of this slogan being shouted circulated on the evening of the 27th, did they?

I don't know if protests usually have this kind of "second climax" pattern, nor do I know if the subsequent escalation of conflicts between police and civilians intensified the contradictions that led to that scene. I really wish I could have stayed longer that day to witness the events more clearly. But regardless, my clear feeling at the scene was that we indeed far from reached a consensus on such significant political demands; even the demands for "scientific" epidemic prevention were not expressed clearly enough.

And the slogans of the Hong Kong people have been clear enough: "Five demands, not one less." The prolonged struggle has been so fierce, yet it ultimately failed. Why should we fantasize that simply shouting for the Communist Party and Xi Jinping to step down can push things forward, especially when this is not a demand that most people agree upon? I believe we should recognize the current situation more clearly, abandon fantasies, and prepare for a long-term struggle.

Of course, whether the road is long depends on where you want to go. When I say the road is still long, it is certainly in reference to the place I want to go—no dictatorship, but democracy.

Things can develop quickly.

Although from the above, it seems I am more pessimistic about our long road ahead, I also deeply feel that developments can often happen very quickly. Even when Shanghai was locked down, my attitude towards "will you join our crusade" was extremely pessimistic; I never expected that six months later, this city would indeed see large-scale white paper protests. But if we reflect on history, whether it’s the collapse of FTX overnight in the crypto world or the protests that spread from the fire in Urumqi to various places across the country, leading to the overnight zero-COVID policy and the overnight lifting of lockdowns, no one expected it to happen so quickly. Even though I was at the scene for a while, I didn't anticipate that it would quickly progress to everyone shouting "Xi Jinping and the Communist Party step down."

In this sense, this is also one of the important reasons I wanted to be on site: I am very aware that many developments can happen unexpectedly quickly, and if the night of 11.26 on Urumqi Middle Road was one of them, I didn't want to be an outsider.

Everything is so romantic.

The memorial with scented candles, skateboards flying in the night, exotic melodies, fine wine in cups, fashionable attire, cameras, young people—everything is so romantic, even the white paper under the phoenix trees in the evening breeze is so romantic. Yes, this is Shanghai. In a daze, I felt this wasn't a protest; everyone gathered together was just watching a live show. We weren't shouting "No lockdown, we want freedom"; we were shouting "Rock and roll never dies."

I can't judge whether there is a so-called "more appropriate" form; indeed, why should struggle always look so tragic and deep? Who says its essence can't be romantic? Who says it can't be led by young people? The power of young people should not be underestimated; but on the other hand, young people generally have less experience facing deeper suffering and less of a working-class temperament. I don't want the white paper we hold up and the shouts we make on the streets to ultimately become nothing more than a frivolous provocation by spirited young people.

After all, the protests in the spring and summer of 1989 were also primarily led by young people and were equally romantic, but they ended in tragedy.

Everyone is filming.

As mentioned earlier, "the vast majority of people were holding their phones to film," which was a bit shocking to me. Besides phones, many people were using professional cameras. The first time I saw this scene, it reminded me of a certain footage about June Fourth, where I remember a panoramic shot showing that there were also a large number of people following and filming the demonstrations on the street. Now, since smartphones are so popular, it seems entirely unremarkable that everyone has become a person filming.

When I saw footage showing that there were indeed a large number of people filming during the June Fourth protests, I was somewhat surprised; I felt it differed significantly from my imagination, making me question whether there was too much showmanship in what was presented to us. But from the moment I arrived at the scene that night, I immediately understood that whether or not we were filming was not important. We were facing the police, the violent machinery of the state, a power that far exceeds us, and what is there to criticize about our right to not give up filming and spreading? Of course, there is an element of showmanship in taking photos, but that doesn't mean the people's roar is fake.

For example, the widely circulated image on Twitter has been criticized by many as staged; I really don't think we need to dig into the details behind these photos. This photo can evoke emotional resonance in people and encourage more to dare to question power and sympathize with the weak, which is enough. Just like the photo of the Tank Man left from June Fourth, after watching the entire video of the event, I felt it wasn't as tragically heroic as that moment in the photo; after all, the tank had stopped restrainedly, and he was eventually taken away. But none of this is important. Rather, most of those widely circulated news photos may not withstand scrutiny regarding the timing and angles of their shots, but the emotions and facts they convey are not false. Of course, precisely because photos may have strong emotional manipulation, we need to pay more attention to the facts and think independently; journalists need to work harder to ensure objective and fair reporting, but the photos themselves certainly have their chosen angles and timing, which is the least worthy of criticism.

Conclusion#

I only stayed at the scene for a short hour, yet I wrote such a lengthy article; perhaps this night truly gave me too many feelings and made me more clear-headed. Now that cities across the country are "lifting lockdowns," I believe this is the result of our collective struggle, but this is certainly just the beginning. Fellow travelers, let us walk together.

Appendix#

For a general understanding, you can refer to Wikipedia: https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/2022%E5%B9%B4%E4%B8%8A%E6%B5%B7%E4%B9%8C%E9%B2%81%E6%9C%A8%E9%BD%90%E4%B8%AD%E8%B7%AF%E6%8A%97%E8%AE%AE

For the overall video of the 26th, you can refer to https://youtu.be/RnFQNC1775M

For what happened before I arrived on the 26th, you can refer to this tweet: https://twitter.com/whyyoutouzhele/status/1596533126200963073

Afterwards, a firsthand account from someone who arrived at 3 o'clock: https://twitter.com/whyyoutouzhele/status/1596609632667324416

For the 27th, you can refer to an interview with someone who escaped after being arrested: https://www.rfa.org/mandarin/yataibaodao/renquanfazhi/wy-11282022094229.html

And the Twitter timeline of Teacher Li:

https://twitter.com/whyyoutouzhele/status/1596782529113378817